How to install website certificates on Linux

https://linuxkamarada.com/en/2018/10/30/how-to-install-website-certificates-on-linux/#.YJAl96L7RH5

Last updated

https://linuxkamarada.com/en/2018/10/30/how-to-install-website-certificates-on-linux/#.YJAl96L7RH5

Last updated

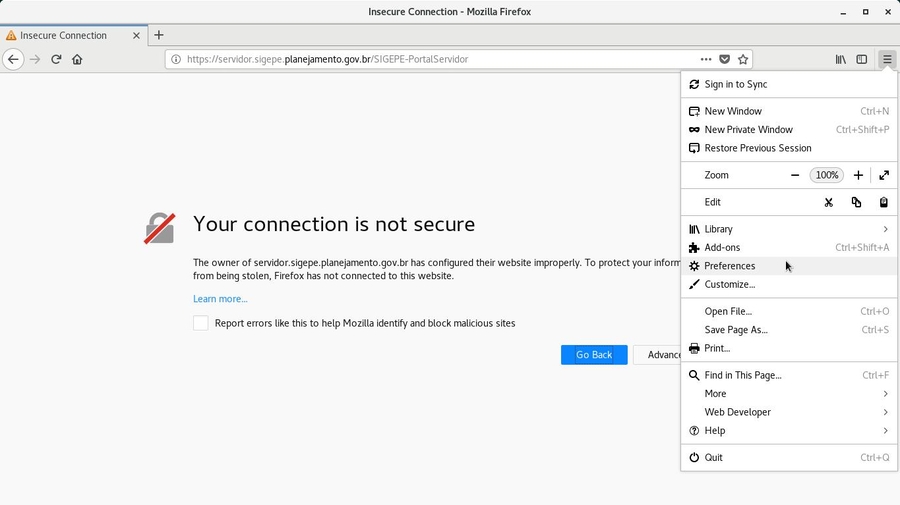

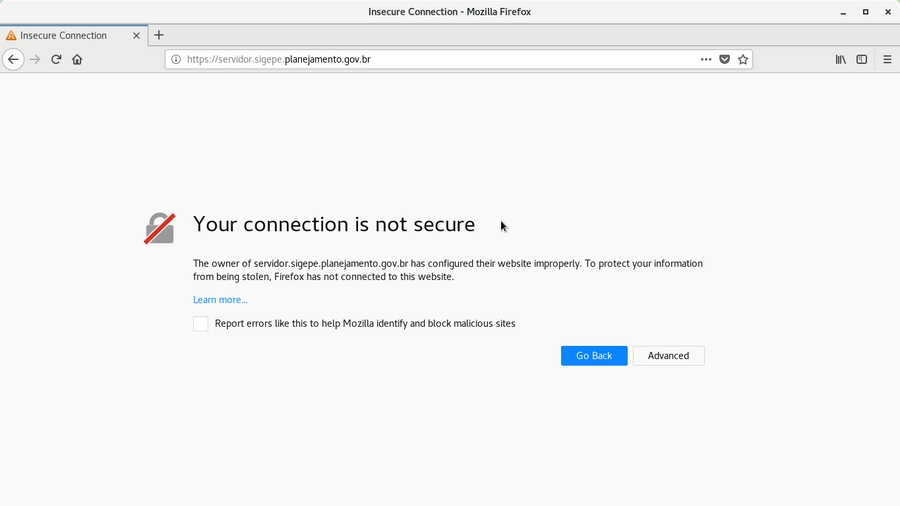

Have you ever visited a website and your browser adverted you that your connection is not secure or private?

When you visit a website that uses secure connection (web address starting with https), your communication is encrypted to help ensure your privacy. Before establishing connection, the website presents to the browser a security certificate identifying itself.

Anyone can create a certificate claiming to be whoever they want. But usually website certificates are issued and signed by certificate authorities (CA’s), which also have their own certificates. On their turn, CA’s certificates may be self-signed (in the case of a company’s internal CA) or signed by other CA’s so forth up to a root certificate authority (root CA). This chain of certificates is called the certificate hierarchy.

Root CA’s are public, well known and trusted organizations, such as the American FCPCA or the Brazilian ICP-Brasil. Usually root CA’s certificates are previously known by browsers.

When you visit an HTTPS website, the browser checks that its certificate is valid and the certificate hierarchy ends on a known CA certificate. If that checking succeeds, the browser displays a green lock icon near the address bar, indicating the website you are visiting is actually the website that it claims to be. You are safe to stay on it, enter passwords, provide credit card numbers and send or receive other sensitive data. Always look for the green lock icon when accessing banking or shopping websites.

When you visit an HTTPS website, but the certificate checking does not succeed, the browser adverts you that your connection is not secure or private. If that is the case, you need to proceed with caution: don’t enter any sensitive information on this page. If possible, leave it.

Sometimes, the connection is not really insecure. Security alerts may appear, for example, when you visit a web system of your organization, signed by an internal CA whose certificate is not previously known by the browser. In that case, you need to manually install your organization’s CA certificate to prevent false alerts.

Also Brazilian citizens always see privacy alerts when visiting websites of the Brazilian government. Browsers don’t come with the ICP-Brasil certificate out-of-the-box because it does not comply to Mozilla security requirements, which is an 11-year old bug. So, Brazilian citizens need to manually install it. Some Brazilian public organizations have adopted workarounds: for instance, the Federal Police of Brazil sign its forms (e.g. the passport application form) with a certificate issued by Let’s Encrypt, but content-only pages (including their own home page) are not signed at all. Let’s Encrypt is an American non-profit organization that issues certificates for free for anyone and is trusted by browsers.

Let’s see how to add a CA certificate to the Mozilla Firefox and Google Chrome browsers, so they trust certificates signed by that CA. Same instructions for Chrome apply to its open source base Chromium.

I’m going to use SIGEPE as example, which is a Brazilian government web system whose certificate is signed by ICP-Brasil, the Brazilian root CA.

In your case, the certificate you are going to install may be from your company’s internal CA. You should retrieve it with your company’s network administrator.

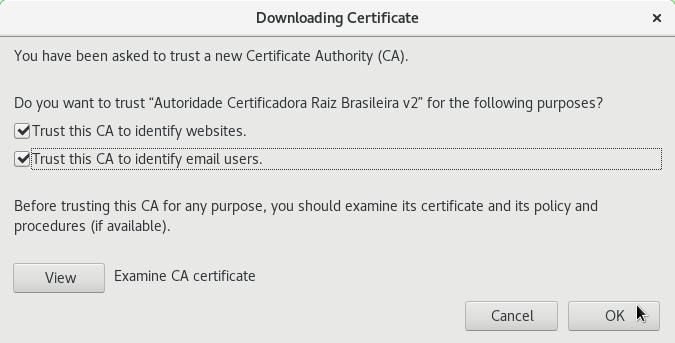

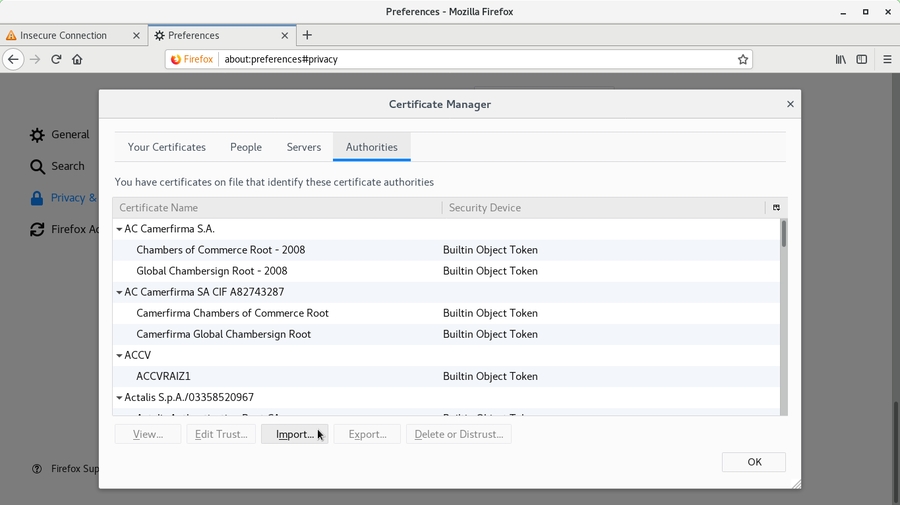

Select the CA certificate file you want to import.

Click on OK in the Certificate Manager dialog and close the Preferences tab.

Select the CA certificate file you want to import.

Close the Settings tab.

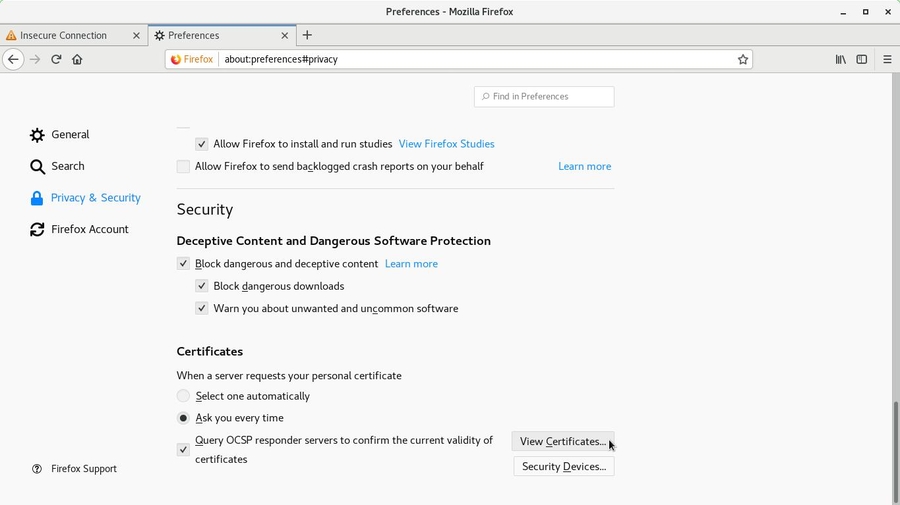

Select Privacy & Security by the left and click on View Certificates by the right, at the end of the page:

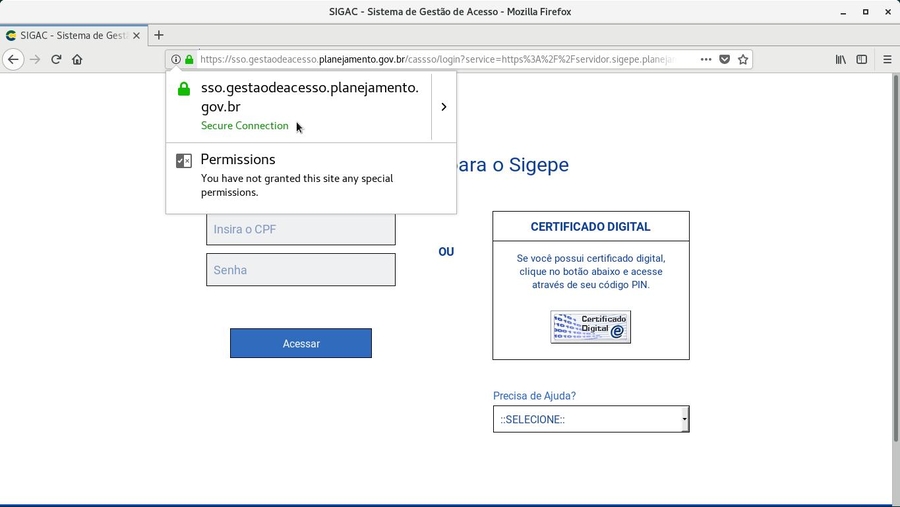

Refresh the page you were trying to visit and realize the green lock icon at the begining of the address bar, indicating the website is safe to visit:

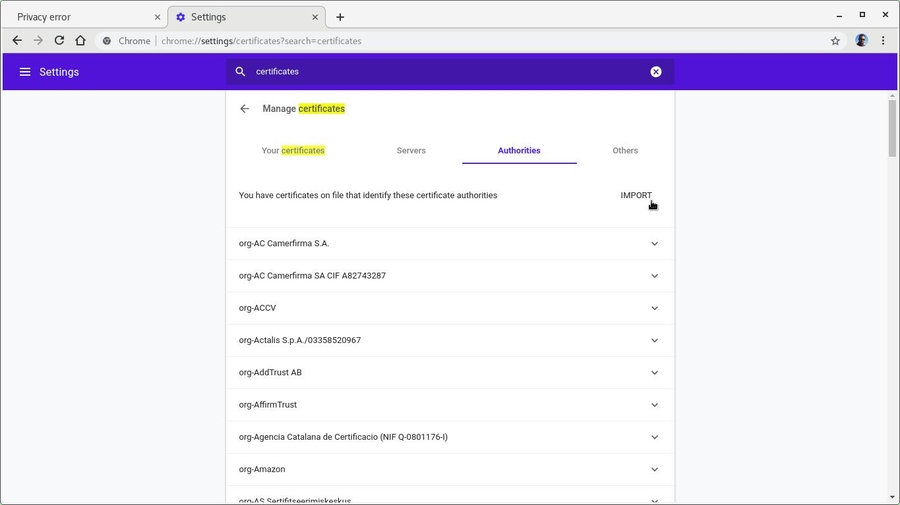

On the Search settings field, type certificates. Chrome filters related settings. Click on Manage certificates:

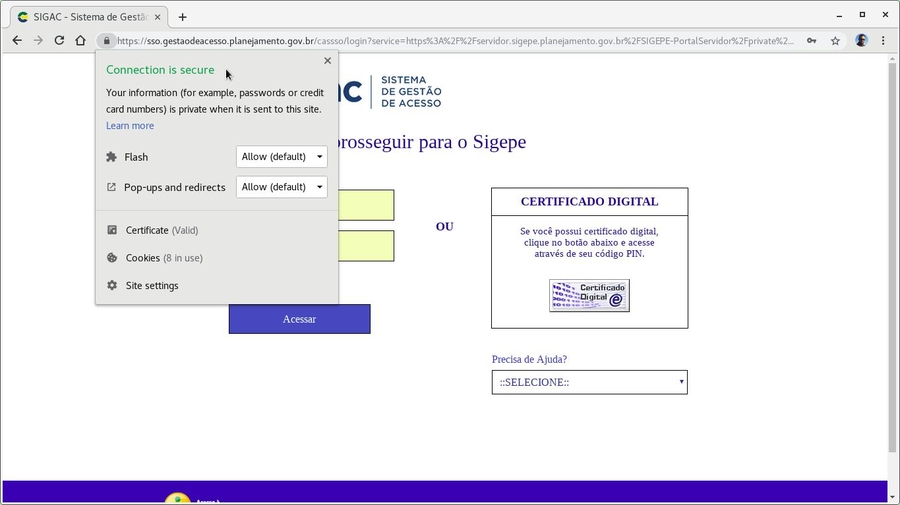

Refresh the page you were trying to visit and realize the lock icon to the left of the web address, indicating the website is safe to visit: